2024. 12. 6. 12:14ㆍCivil Engineering in Australia/Road Design

- Superelevation is primarily chosen for safety but also considers comfort and appearance, taking into account factors such as

- the operating (design) speed of the curve (typically the 85th percentile speed),

- the tendency of slow vehicles to track toward the center,

- the stability of heavily laden trucks (particularly on downgrades or adverse crossfalls),

- the difference in formation levels (notably in flat or urban areas),

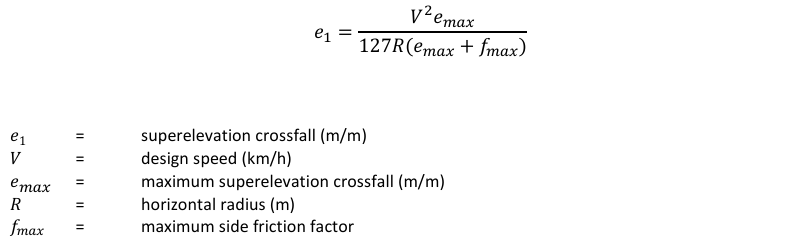

- Linear Method : The linear method for superelevation involves gradually increasing the superelevation and side friction from zero at larger radii to their maximum values at the minimum radius. This approach ensures consistent centripetal force management across different curve radii. For construction convenience, superelevation values are typically rounded up to the nearest 0.5%, with corresponding adjustments made to the side friction. In cases where existing roads are reused, alternative superelevation values may be applied as long as they maintain consistency with the design speed and adjacent curves. The calculated superelevation values, often rounded, are incorporated into the actual design, providing a practical and flexible approach to meet design and construction requirements.

- Rounding : The calculated superelevation is typically rounded up (e.g., 4.1% → 4.5%).

- Side Friction Calculation : Using the rounded superelevation, the side friction factor (f1f_1) is recalculated.

- Flexibility : If specific conditions cannot be met, actual values may be used, and adjustments can be made to the maximum values depending on the design speed and radius.

- Maximum Values of Superelevation : Maximum superelevation values, typically up to 7%, are rarely exceeded in practice, though values up to 10% may be used in urban loop ramps or low-speed mountainous terrain (<70 km/h). In steep or constrained areas, maximum superelevation is necessary but should not justify using small-radius horizontal curves except in specific cases. Factors such as driver expectation, comfort, road safety (e.g., stability of high center-of-gravity vehicles), and environmental conditions (e.g., erosion, icy roads) must be considered. Some road agencies limit practical maximum superelevation to 6% for most roads and 10% for loop ramps.

- Minimum Values of Superelevation : The minimum superelevation should not be less than the normal crossfall of adjacent straight sections, typically 3% for sealed surfaces. For curves, even at lower speeds (<100 km/h), it is generally preferable to apply at least the same 3% crossfall as on straights. On large curves, adverse crossfall may also be considered.

- Length of Superelevation Development : The length required to develop superelevation (LeL_e) must ensure good road appearance and riding quality, with longer lengths needed for higher speeds or wider roads. It represents the transition from normal crossfall on a straight alignment to full superelevation on a circular curve and consists of two main components: superelevation runoff (Sro), the length required to transition from flat to fully superelevated crossfall, and tangent runout (Tro), the length needed to transition from a normal crown to flat crossfall. The lengths are determined based on the pavement crossfall rotation rate and the relative grade between the axis of rotation and the edges of the carriageway, using design values provided in Table 7.11.

- Rate of Rotation : The rate of pavement rotation for superelevation should ideally not exceed 2.5% per second for speeds ≥80 km/h and 3.5% per second for speeds <80 km/h. The minimum superelevation development length is calculated using the formula

In situations requiring better stormwater management, higher rates of rotation—up to 3% for high-speed roads and 4% for mountainous terrain—can be used to shorten flow paths and reduce the risk of aquaplaning.

- Relative Grade : The relative grade is the percentage difference between the grade at the edge of the carriageway and the axis of rotation. To ensure a smooth appearance, this difference should stay below the maximum values provided in Table 7.10. For operating speeds <80 km/h, the relative grade is calculated using a formula with a rotation rate of 3.5% per second, while for speeds ≥80 km/h, it uses a rotation rate of 2.5% per second.

which considers the width from the axis of rotation, the difference in crossfall values, and the relative grade. The calculated values for relative grade are acceptable as long as they are below the maximum limits from Table 7.10.

- Positioning of Superelevation Runoff without Transitions : For circular curves without transition sections, it’s best to place about 70-90% of the superelevation runoff on the straight (tangent) section, depending on the speed. However, practices vary. Research suggests that aligning the runoff with the natural steering path of drivers works well, so placing 50% on the tangent and keeping no more than 30 m (or 1 second of travel) into the curve is common. In special cases, like steep slopes, untransitioned curves, or to control water flow, it’s better to place 80-100% on the tangent. A good compromise for most situations is placing 60-70% on the tangent, still following the 30 m limit into the curve.

'Civil Engineering in Australia > Road Design' 카테고리의 다른 글

| Type of Intersection and It's selection (0) | 2024.12.06 |

|---|---|

| Cross sectional profile (2) | 2024.12.05 |

| Calculation methods for Curve Geometry and Roadworks (0) | 2024.12.03 |

| Vertical Cerves(Sag) (0) | 2024.12.03 |

| Vertical Cerves(Crest) (1) | 2024.12.02 |